Articles

Editor’s Picks

Higher Education

When It Comes to For-Profit Distance Education and Correspondence Courses, History Repeats Itself: Report

By Henry Kronk

December 20, 2018

Over the course of the summer, the Department of Education under Secretary Betsy DeVos made numerous proposals to deregulate the for-profit education industry, a sector that received harsh scrutiny during the former presidential administration. Among these proposals, DeVos initiated the process of doing away with the gainful employment safeguards that ask institutions to publish data regarding the professional success of their graduates, along with the mandate that ensures institutions provide ‘regular and substantive interaction’ between instructors and students. These measures stand to significantly impact the for-profit and online higher education sector. Many policymakers and journalists approach these issues as if they represent new territory. We have never, after all, taught learners via digital technology at the current scale at which it occurs, and that has produced a series of new advantages and disadvantages. But according to the liberal-leaning New America’s education policy researcher David Whitman, the debate over for-profit (de)regulation stretches back to correspondence courses. It is nothing new.

As Whitman writes, “a look back at history reveals that the regulations that Secretary DeVos plans to rewrite or eliminate have their origins in abuses of federal aid dollars by an earlier form of distance education—correspondence programs, the precursor to today’s distance education.”

When eLearning Inside digests the many excellent and well-researched reports put out by American think tanks across the political spectrum, there are typically numerous conclusions or takeaways to glean from them. With Whitman’s The Cautionary Tale of Correspondence Schools, however, there is just one: When it comes to for-profit distance education, history has repeated itself over and over again.

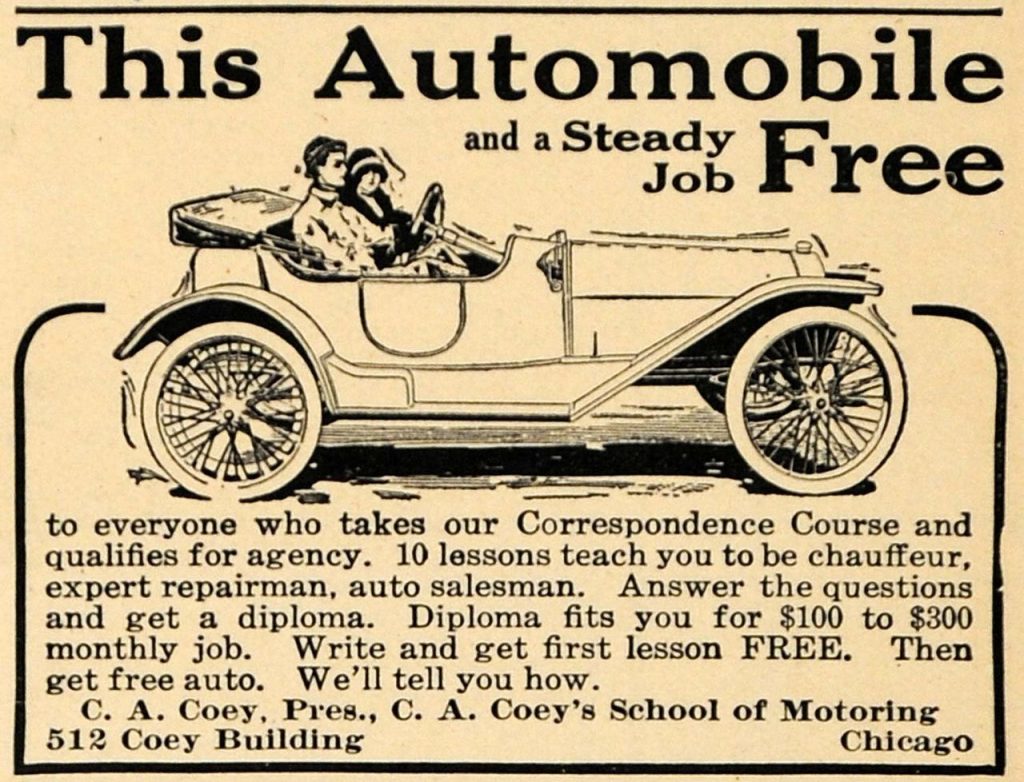

The Beginning of Correspondence Courses and Resulting For-Profit Abuse

Correspondence programs date back to the early 19th century. But widespread for-profit abuses of these programs, according to Whitman, began with the G.I. Bill following the conclusion of World War II.

“In the five years that followed Franklin Roosevelt’s signing of the 1944 law, the total number of for-profit schools in the United States tripled, from 1,878 to 5,635,” Whitman writes. “Thousands of new ones opened to serve veterans, and thousands more, ill-suited to provide an education, closed. Contrary to conventional wisdom, more veterans actually used their educational benefits to attend for-profit schools than went to four-year colleges and universities. And many of those programs utilized correspondence education. While 2.2 million vets went to college on the GI Bill, 2.4 million GIs used their educational benefits to enroll in trade and technical and business schools, with another 637,000 veterans taking correspondence courses.”

Driven by the availability of federal student loans, for-profit correspondence programs typically misrepresented their programs and graduated a shockingly low percentage of their learners. Even fewer went on to find jobs in their area of study. G.I.s, furthermore, frequently gamed the system.

“Tens of thousands of veterans trained for jobs in overcrowded fields in which there were no job openings. G.I.s who wanted to collect their monthly subsistence checks but had no clear educational or occupational objective were allowed to switch willy-nilly from one field to another. And thousands of veterans signed up for recreational or avocational courses, many offered by correspondence, like bartending, personality development, dancing, and auctioneering. Others had the VA pay for TV repair courses and then dropped out of their courses as soon as they got their promised free television. In 1949 alone, nearly 550,000 veterans made course changes.”

Deregulation Begins

By 1950, the Truman administration had grown wise to the abuses of correspondence courses. As vets began to return from the Korean War, increased requirements prevented them from committing the same abuses they had a few years earlier. This caused the number of learners enrolling in these courses to plummet from the 600,000+ WWII vets who took them to just 150,000 in 1954.

While no one collected data about gainful employment following graduation, average debt load, or the number of years to graduation, one thing was clear: The 1955 Bradley Commission, which investigated which services benefited discharged G.I.s, estimated that, “in January 1951 that of the 1,677,000 veterans who attended profit schools, only 20 percent completed their courses.”

“That finding,” writes Whitman, “was buttressed by a 1955 Census Bureau survey of 8,000 World War II vets which found that half of those trained by correspondence said they had not used their training “at all” in subsequent jobs.”

The Cycle Repeats with the Higher Education Act

Availability of federal student loans and the potential for for-profit abuse was again increased under President Lyndon Johnson’s 1965 Higher Education Act, along with subsequent amendments. Under this legislation, for-profit programs were included with public and private non-profit institutions as eligible for all federal student loans.

“By the mid-1970s,” writes Whitman, “the number of students using guaranteed loans to attend correspondence schools and trade schools had increased dramatically, so much so that the federal administrator of the guaranteed loan program was warning in internal memos of the rise of the ‘FISL factories.’ In FY 1970, just one student enrolled at the Commercial Trades Institute (CTI), a correspondence school, with a guaranteed loan; by FY 1973, 50,906 enrollees at CTI had guaranteed loans. At Advance Schools, another correspondence school, the enrollment of students with guaranteed loans increased nearly 67-fold over three years, from 1,209 to 80,891 students.”

But while enrollments increased, correspondence school performance did not. “A March 1972 GAO report,” Whitman writes, “found that 75 percent of veterans did not complete their correspondence courses and only 6 percent of sampled veterans achieved the ultimate goal of finding gainful employment in their field of training.”

Like legislation in the mid-‘50s, Congress again reigned in correspondence schools’ access to taxpayer dollars. This came in the form of a rewrite to the G.I. Bill and increased scrutiny by the Veterans Administration. Some of the regulation looked similar to rules in place today. Correspondence courses were not, for example, allowed any longer to advertise in a deceptive or misleading way. The Senate Veteran Affairs Committee also set requirements for minimum job placement standards.

Over the coming decades, numerous politicians called for an outright ban of federal student and G.I. loans directed toward for-profit correspondence courses. In 1991, Secretary of Education Lamar Alexander wrote the following in a letter to Congress: “The Department generally supports the idea of prohibiting students from receiving Title IV, HEA assistance for correspondence courses, and eliminating the eligibility of schools that offer 50 percent or more of their courses by correspondence. There have been many instances of student aid abuse involving correspondence courses.”

The following 1992 amendment to the HEA took these measures, including the so-called 50 percent measure.

Enter Online Universities

In the mid-90s, according to Whitman, two phenomena changed the game. The first was the advent of the internet and online learning. The second was the increasing financialization of for-profit colleges.

“A few large for-profit college chains had existed before 1992 and had been traded on the stock exchange,” Whitman writes, “but the giant for-profit corporations that emerged by 2001 had no precedent in the industry. At the time of the Apollo Group’s initial offering in 1994, its flagship University of Phoenix had 33 campuses in eight states and enrolled fewer than 27,000 students. Ten years later, the University of Phoenix had more than 225,000 students, including more than 100,000 students enrolled online, a bigger enrollment than any public university in the nation.”

House Speaker John Boehner (R-Oh.) did away with the 50 percent measure in the 2005 budget bill and, by the time Senator Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) launched the Senate HELP committee investigation into for-profit schools in 2010, abuses had again crept into the distance for-profit education sector.

As Whitman concludes, “Today, advocates of online programs claim that the potential of modern-day online learning to revolutionize higher education vastly outstrips that of the correspondence schools of the past. They are right—interactive online learning and high-speed internet open up learning opportunities that the founders of the Famous Writers School never envisioned. In light of that potential, many, including Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, have suggested lifting restrictions on higher education to allow innovation to bloom.

“The innovations of tomorrow will look wholly distinct from the college-by-mail programs of the past and will use more sophisticated technologies. Yet for all those apparent differences, the distance education landscape has been marred by the continuation of past abuses in the last several years, with the rise and fall of several predominantly-online for-profit behemoths that assured vulnerable students they would find well-paid careers in high-tech fields but which failed to deliver on their promises. The cautionary tale of correspondence schools suggests that unfettered access to federal dollars will lead to more scandals in which colleges place their bottom lines over their commitment to education—sullying, instead of burnishing, the worthy cause of innovation.”

Read the full report here.

Featured Image: Joel Fulgencio, Unsplash.

No Comments