Articles

Editor’s Picks

Higher Education

Does Online Learning Improve Equity in Education? And What Does that Even Mean?

By Henry Kronk

April 26, 2019

There are two lines that education stakeholders like to throw around when speaking about online education. They form two sides of the same coin: either ‘online learning can improve equity in education,’ or ‘online learning cannot improve equity in education.’ Zooming out from either of these two premises, there are two corresponding narratives that people tend to believe.

The first is often summarized in headlines: Online learning can improve equity in education. Online learning has the potential to democratize education. Technology is key for boosting classroom equity. These blue sky pronouncements typically fall into the ‘thought leader’ category and likely refrain from making any absolute or data-driven statements.

The second common narrative is far more established by research: online learning replicates the inequity already present in society. Numerous academic studies have, at least in part, supported this conclusion.

The Brookings Institute in 2018 investigated the comment forums in an online course. They found that there was a “higher probability of response from an instructor when a comment is posted by a white male.”

MOOCs mark an educational phenomenon that was often the subject of the first narrative but then migrated to the second. They originally had the potential to democratize education and teach learners all over the world who could not otherwise access higher education. Studies have subsequently found that “80% of MOOC students had at least a bachelor’s degree, 60% were employed full-time, and 60% came from developed countries.”

In 2016, Class-Central.com founder and CEO Dhawal Shah wrote, “there’s been a decisive shift by MOOC providers to focus on “professional” learners who are taking these courses for career-related outcomes.”

In other words, MOOCs don’t represent a rising tide that lifts all ships; they primarily benefit an already-educated class of professionals.

What Is Equity in Education?

The word equity is often used in these contexts. But it does not always mean the same thing or refer to the same group(s) of people.

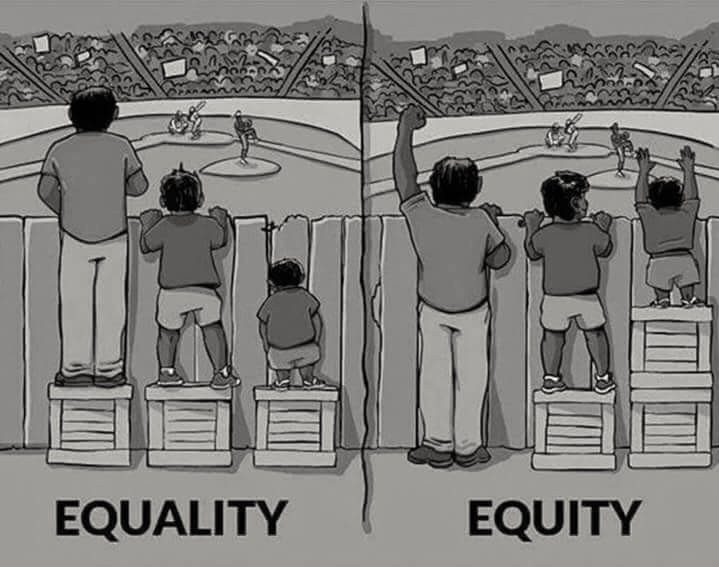

The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines equity as “fairness or justice in the way people are treated.” That isn’t incredibly specific. To describe the term, many contrast it with ‘equality’ and show a version of the image below.

In the context of this article, one might consider the efficacy of online education to be the height of the box. It either allows individuals to look over the fence or it doesn’t. But—what is the fence? Is it improved academic outcomes? undergraduate enrollment? degree attainment? full-time employment in one’s field of study?

A 2016 article in the Stanford Social Innovation Review asked “What the Heck Does ‘Equity’ Mean?” As the authors write: “We recently conducted in-depth conversations about equity with 30 staff members of 15 foundations whose peers named them as leading “equity work” in the field. We found that funders not only are confounded by the definition of equity but also highly desirous of one that resonates—both within their organization and for the field as a whole. Very few foundations had a clear definition of what equity meant to them internally, and absolutely no one saw any common definition emerging from the field anytime soon.”

Many equate representation with equity. For example, while women makeup about 50.8% of the U.S. population, less than a quarter (23.4%) of the House of Representatives are women. The Senate is slightly more equitable: out 100 senators, 25 are women.

But representation as a metric of equity doesn’t map so easily on to education. In terms of undergraduate enrollment, white men are among the most underrepresented groups. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, of the total American undergraduate population was 19,308,000 during the 2016-17 school year (the latest for which data is available). Of that, 56.47% were women. While African Americans comprised an estimated 12.7% of the United States. (according to Census Bureau estimates), they made up 15.57% of the undergraduate population in 2016. Hispanic and Latinx learners represented 19.30% of undergrads, but 17.8% of the U.S. population.

So higher education in the United States is equitable, right? Not quite. The picture flips when it comes to degree attainment. The six-year graduation rate for white students beginning their studies in 2010 was 61.1%. For black learners, it was 38.4% and 50.5% for Hispanic students.

And when it comes to representation among online learners, the situation is even more complex.

In many if not most cases, online courses expand access options for students, but attainment lags behind face-to-face alternatives. That is not a reason to conclude that online learning perpetuates inequity.

A Few Takes on Equity with Online Learning

For example, at the recent OLC Innovate conference, Michelle Pacansky-Brock presented on the California Community College system. The 114 colleges collectively serve 2.1 million students, 28% of whom study online. Achievement in terms of DFW rates (students who receive a D, an F, or who withdraw) lags online. But that achievement gap has been quickly closing. While DFW rates have remained at 70-71% for face-to-face courses since 2006-07, they have climbed online from 53% to 66% during the same time period.

“We in the California Community College system know that online courses are hugely important even though success rates have historically been lower than face-to-face,” Pacansky-Brock said. “To us, that’s not a reason to not do it; it’s a reason to fix the problem. When we look at some of these success gaps, we start to see problems of equity. That’s something we’re very aware of, it’s something we push under the carpet. We talk about it and we try to find ways to improve the problem. We also know that more first generation students typically fall into those particular student groups. Also, students of color are less likely to feel like they belong on campus.“

What’s more, other information indicates that the best secret to success in terms of modality is neither online nor face-to-face; it’s a mix of both.

A 2018 study by Arizona State University and and the Boston Consulting Group titled “Making Digital Learning Work” investigated numerous outcomes, such as retention and access to programs at 6 different institutions that had comprehensive online learning ecosystems.

At Houston Community College, investigators found higher retention rates among online students compared to in-person. But retention among students who took a mix of both was higher than either category.

As the authors write, “Student access to the case study institutions improved on multiple levels, with increases in total student enrollment and increases in the proportions of specific populations, including Pell Grant-eligible students, minority students, older students, and female students.” Qualities such as flexible enrollment also increased access.

So in conclusion, measuring equity in education—and forming a conclusion about online learning’s effect on inequity—is difficult and complicated. Many, having found persistent inequity in online programs, have simply concluded they’re ineffective without realizing any of their benefits.

Featured Image: Erol Ahmed, Flickr.

No Comments